ABSTRACT

When it comes to construction, there is often a rumored ‘information gap’ between the producer and consumer regarding the options. Frankly, this is more than true.

While many have heard of a house in their neighborhood being “offsite,” or their neighbors “prefabricated” shed, perhaps they’ve even witnessed the lego-like process deemed “modular construction,” there is a great number who are unaware of any process besides a traditional build.

Additionally, what many do not realise, is the prefabrication, offsite, and modular methods are, in practice, the exact same thing.

PREFACE

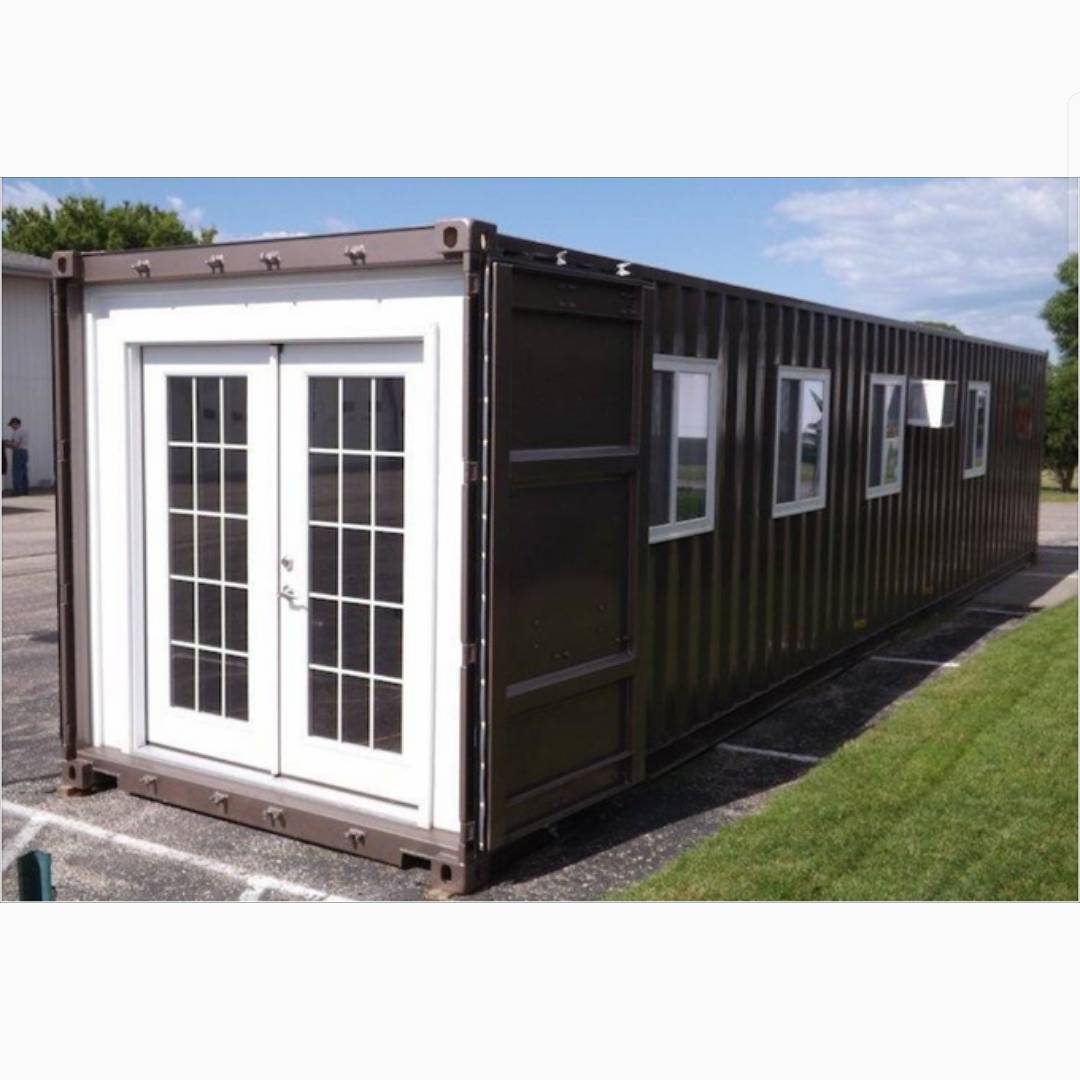

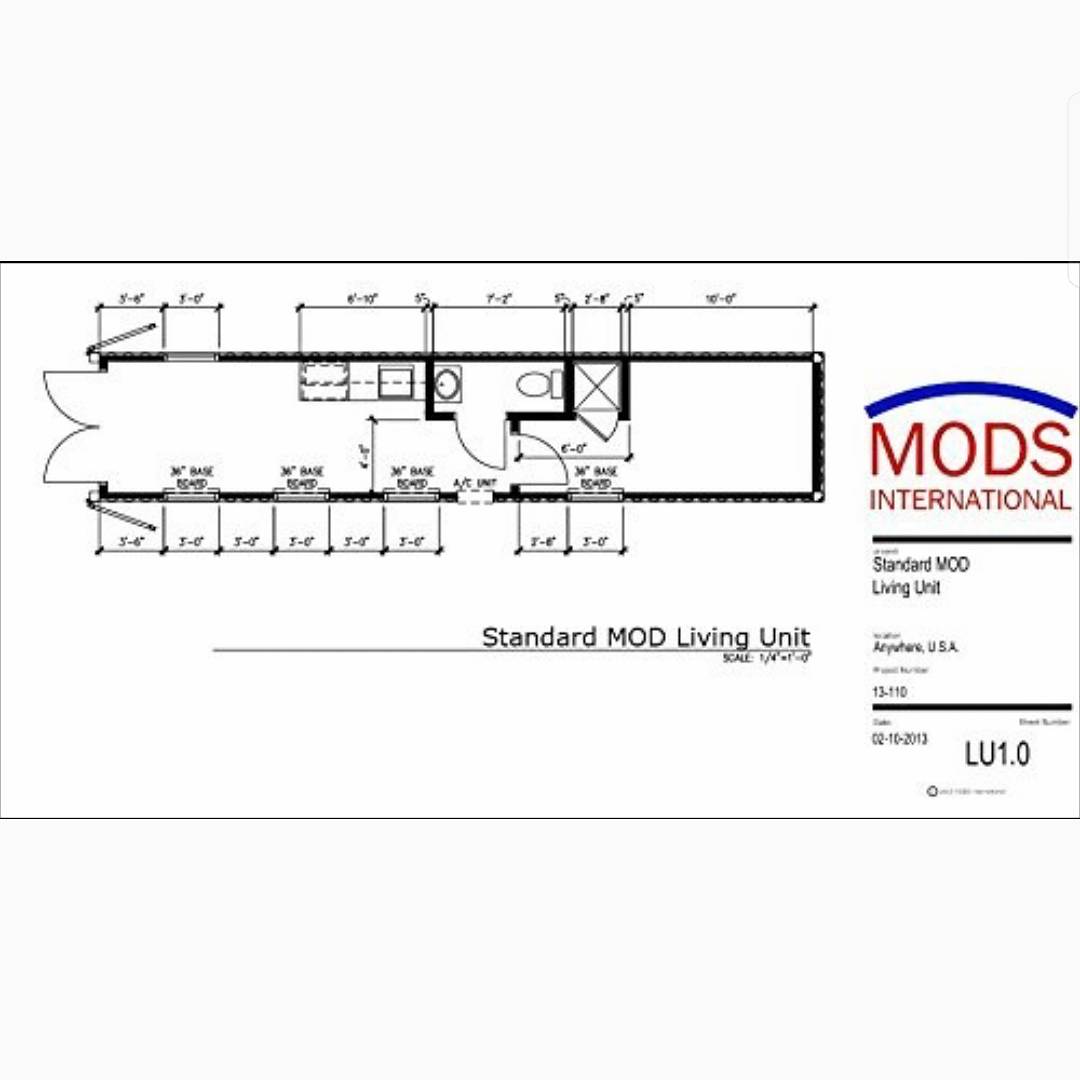

In 2017, one can build a fully furnished home with just as one mouseclick. MODS International (Wisconsin, USA) offers a 320sq ft ‘house’ which comes furnished and insulated (bedroom, shower, toilet, sink, kitchenette, living area, fully wired, heated and air-conditioned, and bottom sewer hookup) for only $40,500 after shipping. MODS’ “Prefabricated Tiny House” can be ordered on Amazon right now (no, it is not offered on Prime).

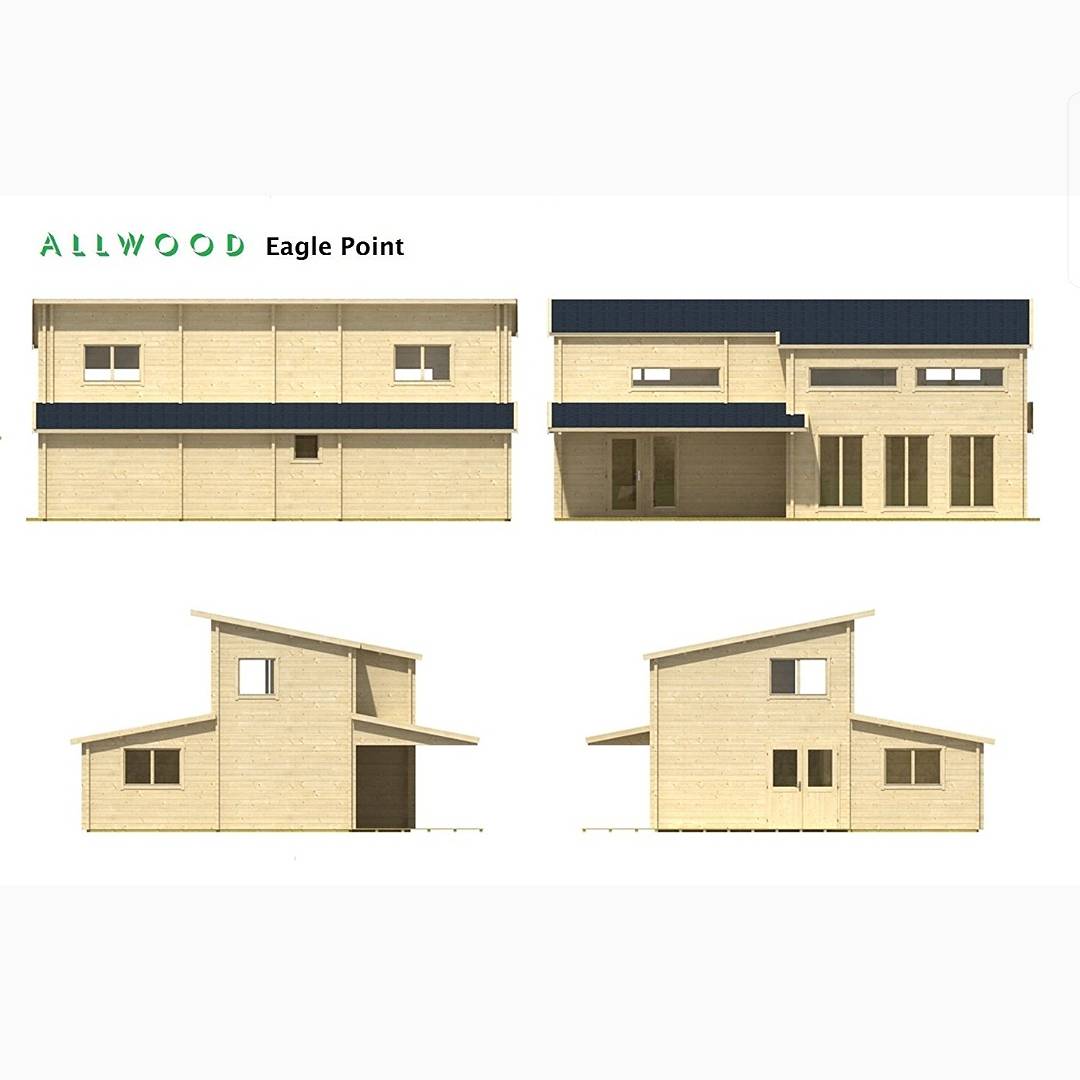

For those looking for a more traditional option Allwood, an importer in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, offers the ‘Eagle Point.’ This “Kit Cabin” provides a more traditional layout than one might expect from a house on Amazon.com.

‘Eagle Point’ is comprised of two stories and comes in at just over 1100 square feed of inside floor area (712 Sq ft downstairs + 396 Sq ft upstairs). Additionally, Allwood generously offers free shipping on this $46,900 investment.

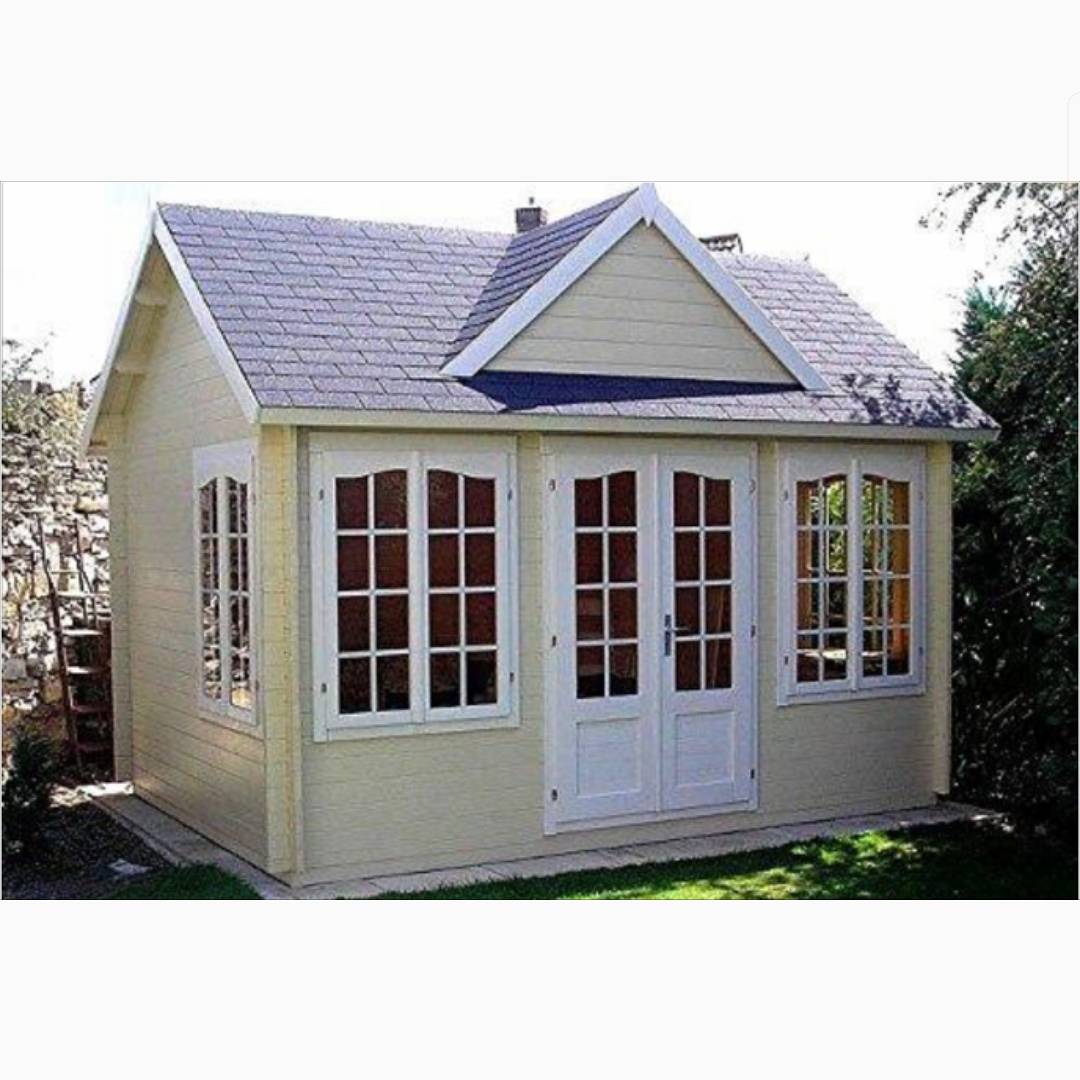

Allwood also lists ‘Chloe,’ another “Kit Cabin” on Amazon as a more compact choice, totaling just 123 square feet. The kit presents an open design, having windows on three sides, and takes just 9 hours to set up (assuming there’s a friend to help, so it might take you a little longer). ‘Chloe’ can be ordered today for a mere $5,490.

In reference to construction, Webster’s Dictionary defines ‘fabricate’ as “to construct from diverse and usually standardized parts,” and ‘prefabricate’ as “1 :to fabricate the parts of at a factory so that construction consists mainly of assembling and uniting standardized parts,” or “2 :to produce artificially.”

Looking at these ready-to-go structures, one might ask, “How did we get here?” And in that, he or she would not be alone as there are countless others asking the same question. The following is a report covering the past, present, and future of prefabricated (a.k.a. offsite, a.k.a. modular) structures.

HISTORY OF PREFABRICATION

Most sources, including the British Museum, agree prefabricated construction began some 6,000 years ago with the placement of the Sweet Track. The track was built on dry land, then, to connect an island in the swamp to high ground; “the rails (long poles) were laid end to end and secured by sharpened pegs driven slantwise into the ground on either side. The planks were then wedged into place between the peg-tops, parallel to the rails beneath, and held firmly in position by vertical pegs.” Due to the efficiency of constructing on dry land, it is speculated that all two kilometers of the track could have been laid in a single day (British Museum, 2017).

According to French historian Pierre Bouet in his book Hastings: October 14, 1066, the earliest known mention of prefabricated buildings and homes comes from verses 6,516–6,526 of Master Wace’s epic poem, Roman de Rou, which, when translated, reads, “They took out of the ship beams of wood and dragged them to the ground. Then the Count (Earl) who brought them, (the beams) already pierced and planed, carved and trimmed, the pegs (raw-plugs/dowels) already trimmed and transported in barrels, erected a castle, had a moat dug around it and thus had constructed a big fortress during the night” (Bouet, 2014).

More reports of prefabricated housing appear in the 16th century under Akbar. In 1579, Arif Qandahari wrote, “his high and majestic nature is such that when he journeys, the tents of His Majesty’s encampment is loaded on five hundred camels. There are eighteen houses, which have been made of boards of wood, each including an upper chamber and balcony, that are set up in a suitable and attractive place. At the time of departure, each board is dismantled, and, at the time of encamping, the boards are joined together by iron rings” (Habib, 1992).

The next documentation is on The Old Planters’ House (Great House) at Cape Ann in 1624. In a letter to Dr. Henry Wheatland, C. M. Endicott conveys, despite the fascinating legend, that the house was “transported through the air by angels from Palestine,” there is “no doubt that it was a “frame house” intended for transportation.” To support this, Endicott identified a marking indicating the house was imported and that “Walter Knight’s testimony had reference merely to setting it up” (Essex Institute, 1860).

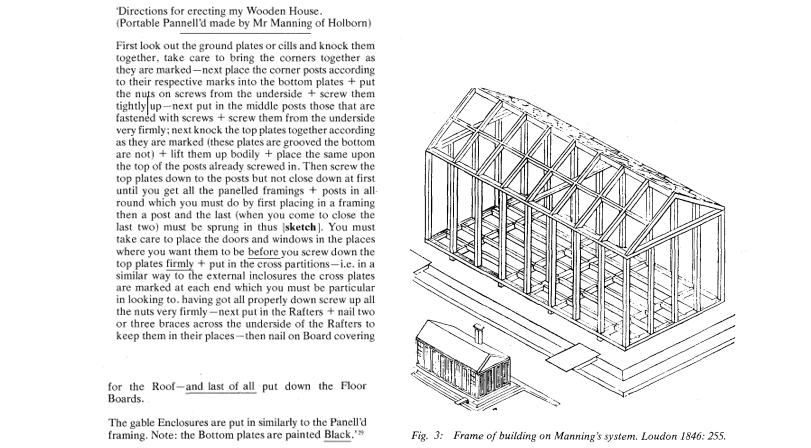

Prefabrication efforts in the 19th century were poorly documented, making it hard to know the specifics of the industry. However, as explained by Professor Miles Lewis in his 1985 report “The Diagnosis of Prefabricated Buildings,” there are hints seen in modular buildings set up in Australia from 1835-1855 which can be used to determine the country of origin, and in some cases the manufacturer, of the remaining projects. For example, materials used and generic marks painted on during transit offer insight as to the country of origin. Other identifiers include catalogue advertisements, use of specific architecture, and documents such as “the inventory of components of one Manning house brought by an immigrant to Victoria in 1852” (pictured with Fig. 3: Frame of building on Manning’s system Loudon 1846: 255)) can be used to credit specific companies and architects.

During the 20th century, mass prefabrication became more common in the United Kingdom. Past examples include: the Iron Bridge built at Colebrookdale in 1779, and the exporting of homes, churches, and hospitals in the middle of the nineteenth century. In the 1920s system-built timber frame dwellings were introduced into the UK market as a response to the shortage of labor in the aftermath of the First World War. This, combined with the desperate need for quick development that could not wait around on traditional building methods, presented the opportunity for builders to experiment with mass prefabrication techniques. Because of the near halt in construction during wartime, a similarly deprived environment arose after the Second World War. Housing standards were low for a large percent of the population, requiring the redevelopment of substandard properties, and the increase in the number of properties available for rent. In 1917 the Ministry of Reconstruction was formed and tasked to “consider and advise upon the problems which may arise out of the present war and may have to be dealt with on its termination” (BRE Scotland, 2003).

Instead of innovation in prefabrication and relying on timber, the Ministry spent their time developing concrete walling to combat the need for an alternative to bricklaying. The only significant advancements of prefab techniques came in the field of steel housing. Due to stagnancy, prefabrication struggled to compete with traditional building, and virtually ceased by 1928. During its tenure after the First World War, prefabrication managed to fill a sliver of the material shortage gap and contribute a small additional number of houses, but made no impact on the long-term market. Following the Second World War, there was once again a shortage of housing stock in the UK. With factories transitioning from war to peacetime operations, there arose another chance for prefab construction to expand, and some factories were adjusted to prefabricate parts of houses. In September 1942, the Interdepartmental Committee on House Construction was commissioned by the Minister of Health, the Secretary of State for Scotland, and the Minister of Works (BRE Scotland, 2003).

According to BRE, “the committee was charged with considering materials and methods of construction suitable for the building of houses and flats, having regard to efficiency, economy and speed of erection. From this consideration recommendations were made for post-war practice. The programme of work agreed was as follows:

- To investigate the alternative methods of house construction used in the inter-war years, and to advise on such methods as might be capable of application or suitable for development in the post-war period.

- To consider the application of methods of prefabrication to house building.

- To examine any proposals put forward for new methods of construction.

- To consider proposals made by the Study Committees of the Directorate of Post-War Building, Ministry of Works, in their relation to house construction.

- To make recommendations for the carrying out or testing of forms of construction by field research or experiment.”

In October 1944, The Housing (Temporary Accommodation) Act was passed. It authorized the government to spend up to £150,000,000 on the provision of temporary housing. An estimated 157,000 temporary houses were put up between the years of 1945-1948. The complete failure of the program severely damaged public perception of prefabrication. One contributing factor to the blunder was a shortage of timber after the war, imposing a ration and limiting the section sizes of timber that could be used in construction. This rationing continued until 1953 (BRE, 2003).

As Great Britain entered the end of the 1950s, Large Panel Systems (LPS) were introduced from Denmark, where they were first developed in 1948. The first structure to take advantage of the new method was for the London City Council (1963), and the London Borough of Newham welcomed nine, 22 story Larsen Nielsen blocks. On 25 July 1966, the construction of Ronan Point block commenced. The structure was completed on 11 March 1968. At 5:45am on 16 May 1968, an explosion occurred four floors from the top of the building. This explosion lifted the top four floors while the flank wall was blown out. As the top floors came down there were no supporting walls to offer resistance and they fell a story before crashing into the floor below (BRE, 2003). This tragedy left a negative association with the idea of prefabrication in the minds of many.

As time passed, that image recovered. In late 2008, NPR published “Prefab: From Utilitarian Home to Design Icon” by Jim Zarroli, who cites that “prefab has fared well in some countries, especially Finland and Japan, where it makes up 20% of the housing market.” Zarroli argues that prefabrication has gone “from fashion reject to in style,” pointing to the exhibit held by New York’s Museum of Modern Art which displayed the history of prefab homes and the possibilities for the future with computer design. With the help of computers, architects are able to adjust and customize builds to fit the buyers’ wants.

The ‘instant house’ designed by MIT’s Larry Sass proves just that. Sass’ structure was one of five prefabricated structures built for the MoMA exhibition on an empty lot next door to the museum. Taking input from buyers, Sass’ computer specifies what kind of materials they need, then the pieces are cut and then numbered for easy assembly (Zarroli, 2008).

Zarroli quotes Barry Bergdoll, curator of the architecture and design department at MoMA, by relaying, “you get four friends — they don’t have to ever have built a house before — and the five of you with five rubber mallets can put the whole thing together in five days.” Bergdol expands, “so if you think about it — what it actually means as a way of thinking — is what I think of as the ultimate technology transfer. The high technology of the MIT computer labs can be sent to a place of no skill and a dwelling of any style you like” (Zarroli, 2008).

Recently, offsite construction has popped up in a variety of markets. Prefabs are being used in Hong Kong to provide some temporary relief to the “150,200 families and elderly people were waiting for public housing, with the average wait some 4.7 years, according to government statistics” (SCMP, 2017). Speaking in the House of Commons in September 2017, United Kingdom Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, Sajid Javid, stated the government’s intention “of making it [modular housing] more pervasive throughout the country” (Marrs, 2017).

While difficult to measure, the UK “offsite fabrication” market was estimated at £800.9m in 2002 (Samuelsson et al., 2003), or 1.7% of new construction (£47.137b in 2002). Later, in 2004, this estimate went up to £2.2b, or 2.1% of the UK construction sector (£106.8b), and was predicted to reach £4b by 2009 (Goodier and Gibb, 2007).

After analyzing 245 financial accounts from industry leaders, Taylor (2010) “estimated that the value of the OSC would contribute between 6% and 7% of construction output and the value predicted for 2013 was £4.8b” Vernikos (2013).

The UK Department for Business and Innovation and Skills (2011) provided data on Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) across the whole construction industry showing a significant decline in the profitability of construction. Although there had been a longer trend of decreased productivity in the industry, profits were unaffected before 2009. Ironically, when profits began to dip, productivity within the industry began to sore (Vernikos, V.K. … et al., 2013). Perhaps this is a method to be tested on the government? This increase in productivity has been accredited to many factors, one of which is the current use of modular construction.

Current Uses

YMCA London South West ‘Y:Cube’ – London

After Boris Johnson signed the MD1242 Mayor’s Housing Covenant – Building the Pipeline funding allocation Mayoral decision was signed on 19 July 2013, £136.5m was set aside and placed toward recipients’ costs of delivering 6,190 homes. Bids were due to the City of London by noon on 21 May 2013. One submission, from YMCA London South West, won funding for the Y:Cube Housing concept designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

According to the YMCA (2015), “Y:Cube uses a pre-constructed ‘plug and play’ modular system which enables the streamlined units to stack easily on top or alongside each other, making it completely adaptable to the size and space available and therefore perfect for tight urban sites. Each unit is constructed from high quality, eco efficient materials (primarily renewable timber), creating accommodation that is so well insulated that they require little or no heating, even in winter months. This presents further valuable savings as the cost of energy rises.

The Y:Cube units are 26m2 studio-like apartments made for single occupancy. They arrive on site as self-contained units and each unit is constructed in the factory with all the services already incorporated, meaning that water, heating and electricity can be easily connected to existing facilities or to other Y:Cubes already on site.”

In September 2015 the Y:Cube design and modular construction were praised by the YMCA, who shared that a majority of renter savings were made possible by offsite construction of the development. The building was up and running after just five months of building. It was also announced that the YMCA is looking to expand and open more Y:Cube schemes across London. With a final cost of £1.6m, and investment from the YMCA London South West coming in just above £1.26m (RSH+P, 2016), the Y:Cube was able to completed with a grant of only £337,000; coming in at £9,361 in grant funding per home, over 60% below the £24,233 per home funding allocated by the Mayor. These savings have been passed on those savings to the consumers, with the apartments renting out at 35% below the market rate in the area (YMCA, 2015).

‘T5 Travelodge’ – Heathrow

To meet the new demand for hotel rooms from Heathrow Airport’s Terminal 5, Sigmat prefabricated this 6-floor hotel comprised of 297 bedrooms with a 150-seat café/bar on the ground floor. The on-site program for this project concluded 2 weeks ahead of schedule in 15 weeks total. Sigmat was able to meet the specifications for high quality maintained by Travelodge.

Pocket ‘Weedington Road’ – Camden

Opened in 2008, this was the first completed Pocket Living scheme. The project created 22 homes for first time buyers or “city makers.” Per Pocket Living, “There’s a secure entrance that opens onto a split-level shared outdoor space, and residents have access to secure cycle storage. All the homes have floor to ceiling windows, fully fitted kitchens and wet-room style bathrooms.”

Midas Construction ‘Twerton Mill’ – Bath

Completed in 2015 (Logo, 2017) and prefabricated by Sigmat for Midas Construction, this student complex, comprised of 330 bedrooms in studio, cluster flats and seven townhouses, could be the future of student living. The project converted a historic Victorian clothing mill into contemporary student living.

Sigmat states that because of the use of their offsite scheme, “patented 18% more structurally efficient light gauge steel frame and Sigmat’ installation teams” on site the development was able to be completed swiftly and efficiently.

Because of the lightweight steel frame, the project used less on site labour, and the structure was up in just 50% the time it would have taken with traditional methods (28 weeks vs 56 weeks on site installation process). Twerton Mill was completed for £17m.

Shetland School – Lerwick, Shetland Islands

Lewick brought in Sigmat to design and construct a three-storey, 100 bedroom residential block for the new Anderson High School. The block is part of a £55.75m contract to build a new school for 1,180 pupils.

The lightweight load bearing steel frame of the building took a 12-hour ferry to Lerwick after being driven to Aberdeen. Even with this, the project was more cost effective than a traditional build. This “superstructure” includes a traditional hot-rolled steel ground-to-first-floor frame, incorporating an external panelized wall system, which was erected in conjunction with the transfer structure. Light gauge steel was used for the top two floors.

Barriers

Lisa Mckenzie, LSE sociology fellow and author of Getting By: Estates, Class and Culture in Austerity Britain, in her article “Dear Sadiq: pocket-sized homes are the last thing London needs.” asserts “the average home in London priced at over £450,000,” meaning new Pocket Living homes could reach “prices of £350,000 to £400,000.” She continues by bringing up that “the average salary in London is £34,995.” According to government data, however, “the median household income for London in 2013/13 was £39,100, while the mean income was £51,770” (London DataStore, 2017).

Either way, Mckenzie is correct with her observation “to afford these homes, on top of the 5% upfront deposit, a person would need an income of around £90,000 to secure a mortgage.” This can be confirmed on moneysavingexpert.com, where it is estimated a single making £90,000 should be able to find a mortgage for £292,500 – £405,000.

Furthering Mckenzie’s argument is the obvious observation that while Pocket homes are only 80% of the cost of normal housing, they are also only 80% (or less) of the size. Philippa Stockley found in her 2015 report for Homes & Property that one room flats by Pocket are 38 sq m (418 sq. ft.), just 76% of the “existing minimum space standard for a one-bedroom new build, which is 50 square metres, or 550sq ft.” In layman’s terms, one would go from paying £1 for 1 unit to paying £0.80 for 0.76 units, losing 24% of the space for only 20% price reduction, which points to the possibility that these prefabricated in-city options might be doing nothing to fix the affordability crisis.

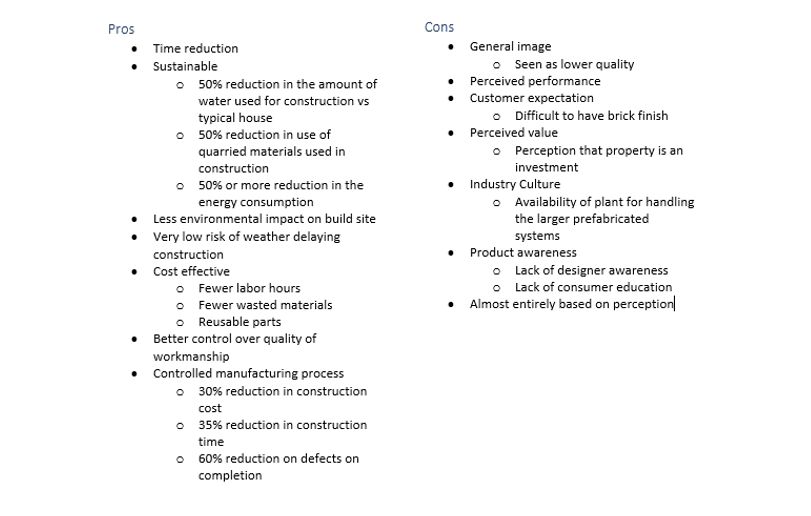

Loughborough University’s Institutional Repository published Implementing an offsite construction strategy: a UK contracting organization case study in 2013. The results of the study found the “most commonly mentioned barrier was the up-front cost to set up a manufacturing facility,” a factor which also affects the number of suppliers. If only using prefabrication, there are limited sources, meaning an error or flaw could reoccur across multiple projects, costing time, money, and reputation. Furthermore, many firms found that contracting external suppliers is just as costly “as if the firm produced its own offsite components.” Offsite was also found to be a concern regarding the image of the firm if “employed where an in-situ or bespoke” solution would better suit the job. An added weight here is the geographical location of the project, “as some projects may be too far for delivering components.” The research concluded that these impact smaller companies and projects exponentially more than larger ones (Vernikos, V.K. … et al., 2013).

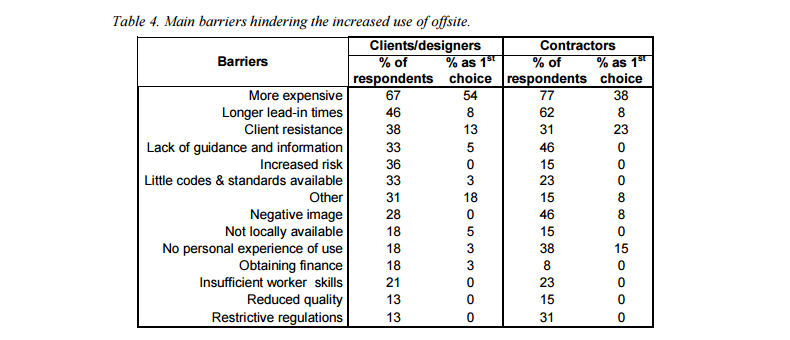

In a comprehensive study, conducted by Chris Goodier and Alistair Gibb, published in 2005 by the Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT) and the Association of Finnish Civil Engineers (RIL), it was found that 97% of clients/designers and 92% of contractors surveyed had used offsite construction in at least one project.

The results of this study also indicated that 65% of clients/designers and 77% of contractors believed offsite to be more expensive, with over half of clients/designers putting this as their first response. Additionally, the survey results indicates that contractors are less educated and more distrustful of offsite than clients/designers, this coincides with the finding that the 8% of contractors who did not answer ‘yes’ to having used offsite before all answered ‘maybe,’ with a grand total of 0% answering ‘no.’

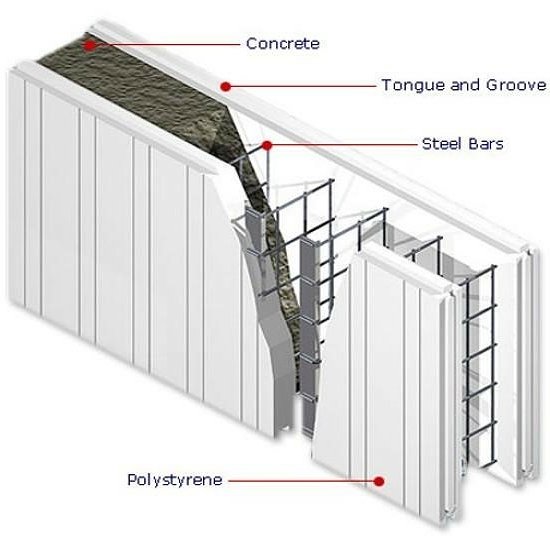

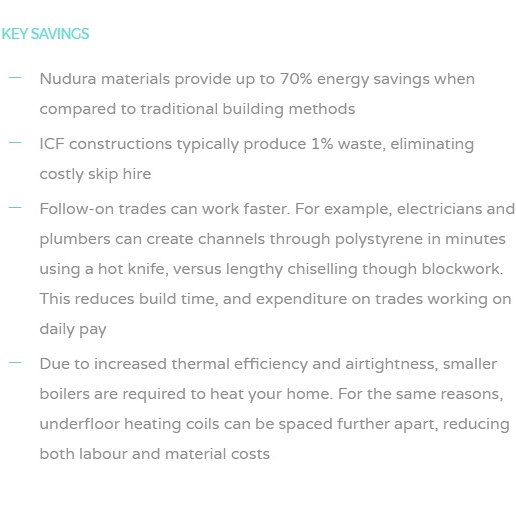

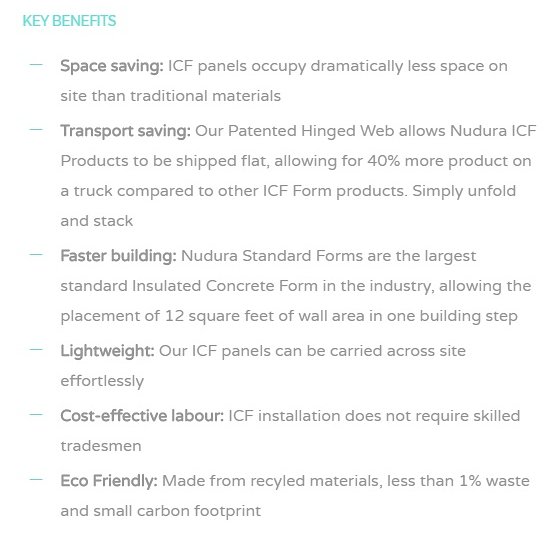

A less frequently discussed, but much more real, barrier to the advancement of offsite in the construction market is advances in technology that are making onsite construction less labor intensive, and more efficient. For example, a plethora of companies, including Logix, Nudura and PolySteel, produce insulated concrete forms (ICFs).

ICFs (diagram below (ICF Supplies Ltd, 2017)) are moulded blocks made of polystyrene. The blocks are lightweight and put together much like Legos. Once laid out to the specifications of any project, ranging from a small shed to multi-story buildings, one simply fills the mould with concrete, and continues construction the next day. Companies advertise that even the most inexperienced builders can construct a house with ICFs. Some go as far as to offer classes and seminars, teaching the average person how to build with ICFs.

It is apparent that there is a stigma associated with offsite or prefabricated construction. While many “problems” related to prefabrication are entirely mental, public opinion has been, is, and will continue to be an unavoidable maker or breaker of any product.

The Future

On October 27, 2017, CRL published “Big Construction Firms Have Their Eyes Set on Automation” by Adriana Blanco. In her article, Blanco covers that because “22% of the current [UK construction] workforce over the age of 50 and numerous construction jobs unfilled across the nation,” many top firms are exploring technological solutions. She adds that Blueprint Robotics already has robots which build walls, roofs, and floors,” and Construction Robotics has developed SAM (Semi-Automated Mason), a robot capable of laying some 3,000 bricks per day. This means that each day SAM lays 600% of the mere 500 bricks laid by the average construction worker. Construction Robotics is looking to bring this technology to the United Kingdom “within the next two years” (Blanco, 2017).

Industry experts, such as David Birkbeck, 17-year CEO of Design for Homes, are addressing these areas for improvement. In a recent interview for Architects Journal, Birkbeck acknowledged, “you need to keep updating and changing” to keep the product relevant. He continued, “making the ground floor and public realm perform effectively will always be a design parameter” as it meets the need for engagement and a sense of community (Marrs, 2017).

London based Legal and General plans to begin producing over 3,000 modular homes each year with after recently opening the world’s largest prefab factory just outside Selby, England. As of February 2017, the factory was building prototype show-homes with the intent to build up to full capacity operating 12 production lines to pump out 10 homes each day. These quick, custom jobs are high in demand as available land decreases throughout metropolitan areas. Firms such as JLL have gone so far as to identify car parks suitable for homes; in fact, JLL has identified space for 400,000 homes in over 10,000 garages without sacrificing parking, and they’re not crazy. Zedfactory Ltd out of Wallington, England has come out with their ‘ZEDPod,’ a self-sufficient build that sits over a parking bay and costs about £65,000 to produce (Yorkshire Post, 2017)

In his recent article “3D Printing and Buildings,” Chris Thompson, Research Engineer at BSRIA Sustainable Construction Group, pointed out that 3D printers, while perceived by many as new technology, have been around for many years. The sudden public obsession with the printers is due to recent improvements in the technology which have made it possible for anyone to have a 3D printer in their home. Currently, 3D printers are used to model and experiment with designs and layouts of projects, but Thompson sees potential for more soon. While many large structures have been 3D printed, getting it down to the ability to mix the materials and parts needed to build a home are still in the experimental stage. Thompson concludes, “the most likely outcome for the near future is in modular construction, making parts of the building in factories and then transporting to and assembling on site.”

Additionally, prefabricated homes could offer consumers a new way to be unique. By simply expanding on Sass’ work or the options provided by HoUSe in Manchester, complete customization of the build might soon be at the buyer’s fingertips.

Many see the changing demographics due to migration as a possibility for the change in social attitudes. As Goodier and Pan (2012) put it, “particularly towards borrowing, owning a home and forming a household.”

With the UK’s socio-economic profile transforming due to an influx of immigrants, ideas of ‘rural lifestyles’ and ‘urban renaissance’ may no longer be the driving forces they were in the twentieth century. High-rise living in the city mixed in with family and community urban living, popular in parts of Europe, might make their way into the United Kingdom (Goodier and Pan, 2012). A current example of this would be Pocket Homes, which are constructed with communal space to encourage engagement with one’s surroundings.

Running with Sass’ concepts, both Toyota Homes and Rapyd Rooms have taken the customization process online. Consumers are able to see different options and kits online, and are then given quotes based on their desires (Goodier and Pan, 2012).

All factors taken into consideration, prefabricated developments are receiving funding and companies are sprouting up all over the world. With more consumer education, and ever-increasing technology in the field of construction and architecture, prefabrication would appear to have considerable leverage and potential for expansion in the near future.

Goodier and Pan (2012) summed it up with, “The future nature and form of UK house building will no doubt remain heavily reliant on land use planning, the national (and as has recently been seen, the global) economy and the variability of the housing market. However, consumer preference, technology and wider sustainability issues will play increasingly important and dominant roles.”

What it Means

In regard to the United Kingdom, the current super-prime property market in London and Brexit have contributed to the dropping of London from #1 on JLL’s 2015 and 2016 City Momentum Index to its #6 position in 2017. However, JLL stands by that “the city has shown impressive resilience following the EU referendum and its inherent strengths in technology, innovation and education continue to support a Top 10 ranking.”

It is hard to determine if developments such as those by Pocket will help both the city and the United Kingdom maintain its momentum, but it would be difficult to argue that they will hinder it. From an investment standpoint, the smaller homes have higher capital value than past options, and with the market inflated the way it is, these developments would be exponentially more expensive without the support of government. Strictly speaking facts, there are more people who can afford 38 square metres for £350,000 than can afford (or even get a loan for) 50 metres for £450,000.

Additionally, living in central metro areas will encourage tenants to engage in and contribute to the local economy. Having neighbors in similar situations of life will lead to bonding and a better sense of community, which is lacking in many cities today. Modular construction presents itself as the easiest way to provide prosperity to the city and opportunity for the social and economic improvement of tenants’ lives.

As for the world, offsite construction has established itself as a predominant market force and is here to stay. With continued use in Eastern countries and expanding use in Western countries, the data needed to take prefabrication to the next level is, if not already here, coming very soon.

While technological advancements have lessened the intensive labor demanded by traditional construction, offsite has won out in many established countries as even with assistance there is still a labor shortage in construction. Furthermore, all of these technologies can be applied in the offsite scheme. After breaking even on the upfront costs, prefabrication has many advantages, including lower energy, material, and labor, costs, and very few, if any, disadvantages that can’t be remedied with a good PR campaign.

All things considered, it would be a task for one to argue that there are no seen benefits of offsite construction and that progress isn’t being made to further improve these benefits. Whether or not Google or Amazon will take advantage of this revolution in data to control your mind is a topic for another day, but for now, it is safe to say that prefabrication (aka offsite or modular construction) is here to stay.

Current Companies

- Pocket Living Ltd (Soho, London)

- Markets smaller living quarters to first time buyers at a discounted to prime rate

- “Our compact Pocket homes are sold outright at a discount of at least 20% to the surrounding market rate. They’re only for first time buyers who live or work locally; we call them city makers.”

- Aims to keep living in London affordable for young Londoners

- Only available to “to local people who earn below a certain amount”

- Small number of Pocket Edition homes are available without restriction to anyone from London

- £25m funding from the mayor of London to expand operations (McKenzie, 2017)

- https://www.pocketliving.com/

- Only available to “to local people who earn below a certain amount”

- Markets smaller living quarters to first time buyers at a discounted to prime rate

- Sigmat (Skipton, North Yorkshire)

- Unique steel profiles which are 17.8% more structurally efficient than standard steel sections

- Standalone LGSF structures for up to 15 storeys

- Series of in house developed and patented steel profiles and fixings

- 100,000 sq ft offsite manufacturing facility

- Up to 1100m² onsite build every two weeks

- Accreditations

- A.W. Structures Limited has been certified by BSI to [ISO 9001] under certificate number [FS 621480], [ISO 14001] under certificate number [EMS 621482] and [OHSAS 18001] under certificate number [OHS 621484].

- SIGMAT Limited has been certified by BSI to (ISO 9001) under certificate number (FS 621480), (ISO 14001) under certificate number (EMS 621482) and (OHSAS 18001) under certificate number (OHS 621484).

- http://www.sigmat.co.uk/

- Unique steel profiles which are 17.8% more structurally efficient than standard steel sections

- SCC Design Build (Stockport, Cheshire)

- Family run company employing over 80 staff

- Workforce are all CSCS accredited.

- 7 acre site features a 157,000 sq. ft. high bay industrial workshop to create large scale concrete structures for a variety of projects

- Supply a range of pre-cast products including cladding panels, stair flights, culverts, retaining walls, slabs, beams, columns, and lift shafts.

- Work alongside architects, surveyors, and main contractors

- Supply of concrete solutions

- High-rise residential projects (including PRS)

- Student accommodation

- Hotels

- Prisons

- Multi-storey car parks

- Can offer complete design, manufacture and installation service

- “Due to our expertise and the fact we build the whole precast concrete solution off -site, we can deliver your project faster than our competition.”

- http://www.sccdbltd.co.uk/

- Can offer complete design, manufacture and installation service

- Family run company employing over 80 staff

- Connect-Homes (Los Angeles, CA)

- Connect-Homes was founded to bring innovation to the modular housing industry

- Aims to:

- Eliminate unnecessary factories

- Streamline the shipping process.

- Ships from California to locations worldwide.

- While a traditional home build can amass 8,000 lbs. of landfill waste, Connect-Homes claims to reduce building waste by 75%.

- Additionally, the company estimates that a home’s accompanying energy-efficient technology and appliances can save owners an average of $3,383 per year.

- http://www.connect-homes.com/

- Aims to:

- Connect-Homes was founded to bring innovation to the modular housing industry

- SIG Offsite (Somercotes, Alfreton)

- SIG Offsite is a division of SIG plc

- Created a process to assist traditional methods used in construction

- Manufacture high homes and other structures under controlled factory environments

- Ready to install on site

- Also produce manufactured components for the construction industry

- Could be a utility cupboard or a finished roof system, right through to a complete building

- https://www.sigoffsite.co.uk/

Special Thank You to our Friends Lucas Ross and Marcy Stave